Since 2011 June 20 has been celebrated as the World Refugee Day. The date was chosen by the UN General Assembly in a symbolic gesture.

First of all, in 2001 the fiftieth anniversary of The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was celebrated. Second, since 1975 June 20 has been celebrated as the Day of African Refugees. It was a manifestation of solidarity with millions of Africa’s inhabitants who were forced to abandon their homes as a result of hostilities or persecution. At the end of 2021 the highest number of refugees or internally displaced persons was registered in Kongo (1,3 million) and Ethiopia (1,2 million). The same year the number of refugees across the world peaked at 90 million people.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine wielded a drastic impact on the situation throughout the world: in the first months of 2022 alone the number of those having to flee from war crossed an astonishing 100-million mark. At the beginning of the summer 2022 over 6 million Ukrainians became refugees with another 8 million internally displaced persons.

Big war, millions of displaced people

At the beginning of World War I each of the warring parties thought that victory was a matter of several months. Nobody thought that hostilities would drag on for over four years.

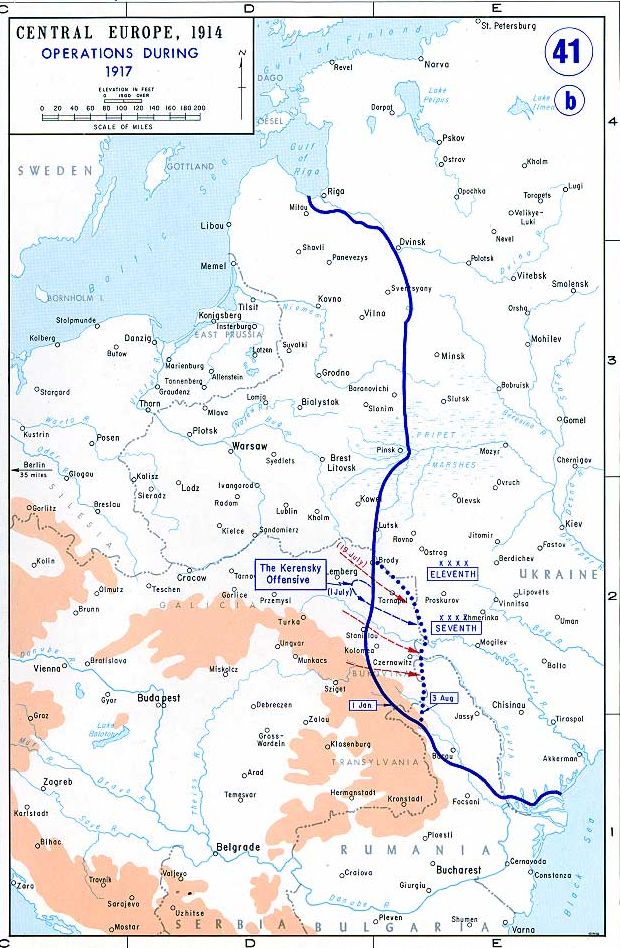

Along a colossal scale of hostilities, a true refugee drama unfolded. Neither Entente nor Central Powers had come prepared to hundreds of thousands of people escaping from the territories located close to the front line.

At the beginning of the war over 200 thousand people relocated from Belgium to England alone. From the territories of Prussia and Alsace about one million civilians fled from war. Vienna saw a major influx of thousands of internally displaced persons from across the Habsburg Empire. None of the governments would have imagined the number of forcibly displaced persons reaching millions of people. Transport, temporary accommodation, makeshift kitchens and canteens had to be urgently arranged.

Movement of refugees reached its peak on the Eastern front that stretched for hundreds of kilometers between the Black and Baltic Sea. According to the estimates of present-day researchers, 5 million of refugees and internally displaced people found themselves in the territory of the Russian Empire alone1. These were mainly rural residents who were moving to the East on their wagons while carrying their most valuable belongings with them, fleeing from war.

Refugees from Volyn (a region in northwestern Ukraine – translator’s note) said that they ‚put a chest full of clothes, towels and rugs on a wagon, as well as barrels for bread, a shovel for digging out earth to plant grain, a barrel with lard, a bag of flour, a regular shove, an ax and a saw. The wagon could not fit anything else’ 2.

Civilians living close to zones of combat would be relocated by rail. However, the network of railroads in the Russian Empire was projected in a way so that its capacity would be higher when goods were being moved eastwards. The traffic westwards was three times as slow, which led to rail jams with railway stations teeming with mostly women and children. Men would be conscripted into the army or used to complete supplementary work.

Almost the entire volume of aid meant for refugees was taken care of by public charitable organizations. Hоwever, they received substantial financial support from the government. The all-Russian Zemstvo Union, the all-Russian Union of Cities and a wide range of international charitable organizations established a network of aid points for refugees and internally displaced persons. At first, refugees would be provided with basic necessities, such as food, clothes and temporary accommodation. Later on they were helped in their search for a job and a new place of residence. The main aid points in Ukraine, where forcibly relocated refugees would settle down, were located in Kharkiv and Katerynoslav (the present-day city of Dnipro) and the eponymous governorates (major and principal administrative subdivision of the Russian Empire – translator’s note).

After the first year of the war a Russian government official Alexander Krivosheyin wrote, ‚Out of all vicissitudes of war the advent of refugees is the most unexpected, serious and hard-to-treat problem… Wise German strategists stand behind this influx to intimidate their adversary… Diseases, sorrow and poverty accompany refugees in Russia. They cause panic, destroying everything that had been left after the initial days of the war. These are swarms of insects. Roads are being destroyed, it will soon be impossible to deliver food… The next migration of people in Russia will plunge the country into the darkness of a revolution’. 3

A significant flow of refugees was not only about a voluntary escape from war. The military leadership of the Russian Empire also resorted to forcibly relocating its citizens from the settlements located close to the front line deep into the interior of the empire.

German colonists were the first to be deported. They lived near the hostility zones and were considered as potential collaborators A total of more than 300 thousand of Germans were forcibly relocated. Even so, these were not only the Russian military who deployed such an approach. German troops would also relocate Poles and Jews, while the Habsburg army deported Serbians.

Not until after World War I were international initiatives launched aiming at solving the issue of refugees and displaced persons. One of such organizations was the Nansen International Office for Refugees. However, interwar organizations did not manage to work to the full.

World War II: evacuation, deportation, expulsion

Even now researchers are not able to find out the exact number of refugees, internally displaced persons, those evacuated and deported during World War II and the following wars fought in Europe. For instance, British researchers have suggested the figure of 65 million people who were forced to leave their homes 4. Resettlement of people had reached an unprecedented scale.

It was in the wake of WWII that the well-known acronym DP (standing for a ‚displaced person‘) appeared.

At the end of 1939 approximately 2 million of inhabitants residing in the occupied (by Germany) swathes of Polish territory became refugees and displaced persons. These were mainly Poles expelled from ‚historically German lands‘. In the Soviet Union people living in the occupied territories were also being driven out. The number of displaced persons reached 1,5 million. Many of them were forcibly relocated deep into the interior of the USSR.

During 1941-1942 the Soviet Union embarked on an evacuation unseen before. The government relocated industry enterprises and material values. The scale of resettlement of the population was unprecedented. Soviet researchers noted that during 2 years about 26 million people were forcibly relocated into the vast interior of the USSR 5.

The organization of this process was very poor. The Soviet railway system bore the brunt of it. There was a catastrophic shortage of locomotives and cars. The situation at the railways descended into chaos. The journey that would normally last a few days in peacetime could last for weeks. There was an acute shortage of water, food and medical aid. Refugees were dying in droves. However, even now it seems impossible to ascertain the exact number of casualties caused by the evacuation. Nobody was keeping track of them at that time.

A Soviet bureaucrat, Nikolai Patolichev, wrote in his memoirs, ‚It happened sometimes that people would travel in open cars or on platforms, standing next to machine tools or construction materials, or maybe some of the belongings of the evacuees. In the best-case scenario, 2 or 3 roofed cars would be allocated for transporting women and children. Instead of the seating capacity of 36 passengers, these cars were packed by 80-100 people’6.

International aid

During the entire war mass deportations, expulsions or forced-labor relocations took place. For example, there were 13,5 million forced laborers in Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945. Among them there were prisoners of war, prisoners from concentration camps and millions of men, women and children who were forced to work in the industry, at construction sites or farming. These were the so-called ‚Ostarbeiter‘ 7.

The whole of Europe was thronged by millions of refugees. The situation became critical. In order to rectify it at least to some extent, extensive international cooperation was necessary. To this end member states of the anti-Hitler coalition founded the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. During 1943-1947 it helped over 8 million people. However, this help was insufficient. Different kinds of aid for refugees were also provided by many religious and public organizations that continued to operate in Europe.

In 1947 the organization was renamed into the International Organization for Migration. 4 years later a news transformation took place – the organization called the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was founded. It continues its operations till this day. In 1951 its staff numbered 30 thousand employees with a budget of 300 thousand USD. In 2020 its annual budget exceeded the mark of 8 billion USD8. The aforementioned organizations provided significant help for displaced persons in the wake of WWII.

According to rough estimates, after WWII there were over 20 million of refugees and displaced persons in continental Europe alone.

These were both Jews, who survived the Holocaust, and German civilians who had abandoned their destroyed cities, and prisoners of war from different armies. There was also a tremendous number of forced laborers who had been working in Nazi Germany and temporarily occupied territories9.

Makeshift camps for forcibly relocated people began to be constructed in Europe. To accommodate everyone, lots of options were used. Refugees and displaced persons were accommodated in barracks, factories, airports, hotels, castles, hospitals, private houses, children’s summer camps or even in half-destroyed buildings. Millions of people were awaiting their future after the war.

One of the solutions to the problem was found in repatriation, or sending refugees to their native countries. This idea drew particular support from the Soviet Union, which had incurred colossal losses of civilian lives, needing human resources for its recovery.

All returnees were subjected to checks and filtration procedures carried out by Soviet secret services. Migrants would leave one camp only to find themselves in another one, this time owned by the Soviets.

One of the female returnees wrote in her letter,

‚It’s November 1 today and I am still in Volodymyr-Volynskyi (a city in northwestern Ukraine – translator’s note). You can’t imagine just how many people there are here. There’s lack of dugouts, lack of space with people living outside the barbed wire across the entire field. There are about 200 people living in our dugout. We’ve got no electricity. To fetch water we have to cover a distance of about a mile. Your belongings get stolen wherever you put them. There is no place where you can do the laundry. You can’t wash yourself, either. The camp has no conveniences for people whatsoever. We get food in the form of a dry ration and there’s nothing that we could possibly use to cook it. Pardon me for these details, Stepan, but can you believe it that we don’t even have a toilet here?’ 10.

After the war deportations and forcible relocations continued. The process of resettlement, repatriation and migration dragged on for years with their echoes making themselves felt for more decades to come.

The Balkan crisis

Prior to the 1990s there had been no major influx of refugees or a large-scale resettlement of populations. The gravest post-war migrant crisis was that in the Balkans. It also came down in history as the Yugoslavian wars of 1991-2002.

In 1991 a new wave of forced migrants from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina swept over Europe. During the next few years the number of refugees and displaced persons reached 2 million 11. From 1991 to 1995 the UNHCR embarked upon the most ambitious mission in its history whose budget reached over half a billion USD. In total, during the 1990s more than 4 million civilians living in the territories of former Yugoslavia received aid. First of all, basic necessities were provided, such as food, medical assistance and shelter. Thanks to a wide network of migrant centers thousands of lives were saved12.

The end of hostilities, however, did not augur the end of privations faced by civilians. For many people these migrant centers became home for many years. For example, a Bosnian woman (who is now 78), whose relatives were killed in the Srebrenica massacre, has spent 22 years living in different migrant camps. Some migrants have managed to adapt to living in new conditions. Another Bosnian woman, who was 16 when the war broke out, said, ‚By the time I turned 25 I had already received lots of help. I have been through all the horrors of war. At the same time, I have also experienced kindness shown by strangers’13.

Sources:

1. Kurtsev A. N. The number of refugees in Russian regions in 1916–1917 // Russian South in the past and the present: history, economy, culture. Collection of scientific work of the 4th International scientific conference, December 8, 2006 in two volumes, volume 2, Belgorod, 2007, pages 128-129

2. Quote from Zhvanko L., Refugees of WWI: Ukrainian experience (1914 – 1918). Kharkiv, 2012, page 45

3. Quote from Zhvanko L., Refugees of WWI: Ukrainian experience (1914 – 1918). Kharkiv, 2012, page 27

4. What happened to people displaced by the Second World War? https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/what-happened-to-people-displaced-by-the-second-world-war

5. Belonosov I.I. Evacuation of civilians from the front line settlements in 1941-1942// Echelons heading East (on history of resettlement of industrial capacity in the USSR). Moscow, 1966, page 16

6. Patolichev N.S., Maturity test. Moscow, 1977, page 216

7. Pastushenko T. Ukrainian forced laborers in the Reich: how many of them were there? http://www.historians.in.ua/index.php/en/doslidzhennya/253-tetiana-pastushenko-ukrainski-prymusovi-robitnyky-v-raikhu-skilky-ikh-bulo%20-%200,5

8. https://geneva.mfa.gov.by/ru/interorg/BLR_HCRR/

9. Kubic M. A refugee looks back: What the 1940s teach us about today’s crisishttps://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/the-post-obama-world/a-refugee-looks-back-what-the-1940s-teach-us-about-todays-crisis

10. Lysenko O. Crossed paths: refugees, displaced and internally displaced people in Ukraine in 1939-1940, page 83

11. Ambrozo G. The Balkans at a crossroads: Progress and challenges in finding durable solutions for refugees and displaced persons from the wars in the former Yugoslavia https://www.unhcr.org/4552f2182.pdf

12. Young K. UNHCR and ICRC in the former Yugoslavia: Bosnia-Herzegovina https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/781_806_young.pdf, Feller E. 50 years of international protection of refugees: problems of their protection in the past, present and future // International magazine of the Red Cross, collection of articles, 2001, page 9013. Mihaljevic M. Refugees of 1990s conflicts come home to some comfort https://www.unhcr.org/ceu/10829-refugees-of-1990s-conflicts-come-home-to-some-comfort.html