At the beginning of the 20th century the charitable cause in the Ukrainian lands was gathering much steam. The number of philanthropic initiatives was increasing, as was that of philanthropists and benefactors. One would think that society was gradually tackling main social problems (famine, orphanhood, poverty, etc.). However, a long tradition of charity in Ukraine was abruptly and violently aborted by the Revolution of 1917 and the following events of the Civil War in the territory of the then Russian Empire.

A new lease of life

At the end of June 1918 Moscow hosted the all-Russian congress of commissars for social welfare. The participants of the congress discussed a quite important issue of how they were supposed to go about dealing with the property of charitable organizations that had been operating in the territory of the former Russian Empire. Without thinking for too long, the commissars came up with a proposal to nationalize all of their property. During the next several years the charitable organizations were automatically put under the command of the Commissariat for social welfare including ‘all their assets and equipment’.

Such a decision was based on the Soviet interpretation of charity, which was referred to as ‘a concept foreign to the social regime of the USSR’. Charity turned out to be a superfluous thing for the Soviet government. It was replaced by state authorities that undertook to solve all social problems. Moreover, charity was slammed as ‘assistance hypocritically provided by the representatives of ruling classes of an exploited society for a segment of destitute populations with a view to deceiving the working people and distracting them from taking on class struggle’ .1 This was an approximate definition of charity typically deployed by the Soviets.

The Ukrainian philanthropists after 1917

Since the Soviet government thought of charity as ‘a relic of the capitalist regime’, there was no place for philanthropists and benefactors of the new state. The Soviets went further to declare the former benefactors as class enemies. These ‘enemies’ were left with two options – either to emigrate or to stay and be subjected to constant pressure exerted by the state.

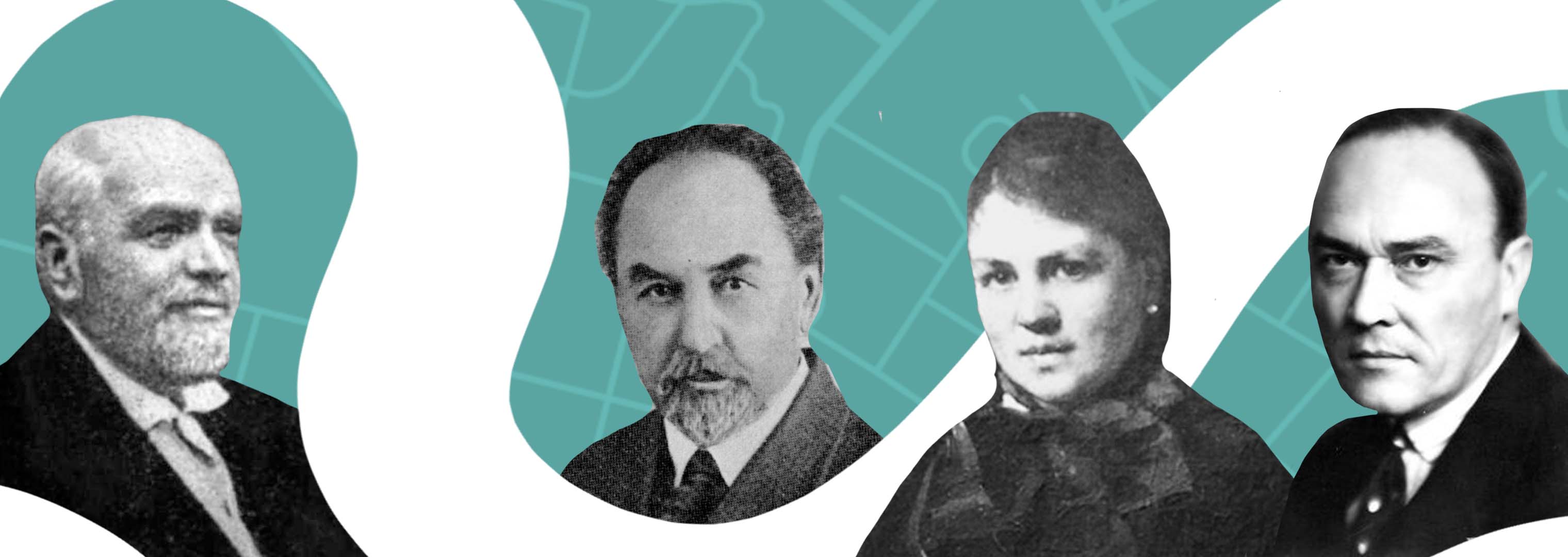

The majority of them opted for the former. For instance, a well-known Ukrainian public figure, benefactor and philanthropist Yevhen Chykalenko, left Kyiv in January 1919 року and went on to spend over 10 years as an emigrant, first in Austria and then in Czechoslovakia. He turned 57 as of the time of his emigration. He lost all his fortune and property. Chykalenko’s life abroad was beset by constant impecunity and health issues. He cherished no hopes for returning to Ukraine, always fearing that the Bolsheviks would ‘have him executed by a firing squad for counterrevolution’.

At the beginning of the 1920s Chykalenko wrote in one of his letters to another Ukrainian public figure, Yevmen Lukasevych, ‘I have no intention of bragging, I am telling you this quite sincerely – it’s a pity I have not died this time. I am of no use to anyone – neither for myself, nor for my kids, nor for my country. It would be good to die at exactly this moment, as long as I know that all my nearest and dearest are alive and that I have food to eat tomorrow’. 2

Despite this, Chykalenko kept working. While living abroad he wrote voluminous memoires. The Terminological Committee of the Ukrainian Commercial Academy in Czechia, issued a few dictionaries under Chykalenko’s tutelage.

The Tereshchenko family and their road of emigration

The path of emigration was pursued by nearly all members of the Tereshchenko dynasty. For example, Mykhailo Ivanovych Tereshchenko was incarcerated right in the wake of the October Revolution of 1917. Only in the spring of 1918 did he manage to get released and emigrate, first to Norway and Sweden, and then to France and finally over to England.

Mykhailo Tereshchenko lost all his assets and property. Worse still, he was stripped of all his possessions located in the territory of other European countries by international creditors. Tereshchenko pawned all of his family’s property to obtain loans for the Russian government toward the war effort.

He had to start with a clean slate. While abroad Tereshchenko managed to prove on several occasions the fact that he was not deprived of talents or of the entrepreneurial spirit. He first worked with a Swedish financial group ‘Vallenberg’ and then with the Norwegian firm ‘Madal’. In the 1930s Mykhailo Tereshchenko made a name for himself in the circle of European financiers. He successfully cooperated with Italian and Austrian banks, in particular with the Rotschild’s representative bank in Vienna. He was regarded as one of the best professionals in the field.

It is not for nothing that the obituary of Mykhailo Tereshchenko published in the London newspaper The Times read, ‘The circumstances that might well have led to a frailer person’s perdition served a means for his triumphal victories. Born into an affluent family, at 30 he had lost everything. It was thanks to his relentless work that he managed to attain power and become influential, having also established a reputation of an absolutely honest and incorruptible person. His death is a great loss for the representatives of the financial circles of many European capitals’.3

At the same time the name of the Tereshchenko family merited quite rare mentions in Soviet Ukraine as of ‘the representatives of the class of exploiters’, ‘moneybags-millionaires’ or ‘famous capitalists’.

A rare object – The Khanenko family

Unlike many other families, the Khanenko family stayed in Ukraine. Right at the beginning of the whirlwind events of 1917, in June, Bogdan Khanenko expired. However, prior to his death he had entrusted his wife with a very important and difficult task. According to his will, Varvara Khanenko had to establish an art museum in Kyiv that would exhibit the pieces of art from the family’s collection. By that time Mrs. Khanenko had already turned 65. She refused to emigrate or to take the rich family’s collection abroad.

Finally, in December 1918 Varvara Khanenko concluded a gift contract transferring ownership of the collection and of her own house to the Ukrainian Academy of Science. Several key conditions were included into the contract: the future museum would have to bear the name of Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko with the latter being allowed to work in the museum and live in its premises till her dying day.

After the Soviets came to power all of the contractual arrangements were forgotten.

Mrs. Khanenko was rightfully appalled complaining that, ‘(I) do not deserve to be dishonorably evicted from the museum the ownership of which I transferred to the state in perfect condition. I have made an official statement that I categorically refuse to leave this room of my own will, the room that I live in and where I have spent most of my life. They will only be able to evict my dead body, that is to say, by leading me to commit a suicide’. 4

Soviet scientists would claim that ‘Varvara Khanenko could surely not sympathize with the Revolution due to her psychology of classes. She took the end of the old regime too hard’. Therefore, she was ranked as a class enemy belonging to the group of industrialists and capitalists with her charitable contribution having always been slurred over. In the end, the Soviet functionaries did drive the woman out of her home. Varvara Khanenko spent her last months living in a flat of her former servant girl. She passed away in May 1922. In December 1923 the name of the museum was deprived of the ‘named after Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko’ part.

Pototsky and lost arrangements

Another prominent cultural figure who chose not to emigrate in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1917 was Pavlo Pototsky. He was descended from a Cossack dynasty living in the Poltava region, Ukraine. He made a dazzling career of a military man, having achieved the rank of an artillery general. At the same time he was fond of history and collecting art objects. Pototsky retired in the capacity of a general in 1917 and continued living in Petrograd. Despite the fact that both of his sons had emigrated, Pototsky decided against it. Apparently, he was concerned about the fate of his unique collection of works of art and books on Ukraine’s history and culture. These were Soviet officials who provided in 1925 the following character reference of the general, ‘Pototsky is a typical philanthropist and collector of ‘good olden times’, which he has managed to compile thanks to his considerable wealth (being a solid landowner) in form of a large and valuable unit’. 5

In the middle of the 1920 Pototsky decided to give his unique collection away to the all-Ukrainian Academy of Science. However, the philanthropist had set out several conditions: the collection was not to be scattered, he was to be granted the right to live and work in the museum, he was to be provided with a state pension and his family was to be provided for after his death.

In the end the arrangements were agreed upon and in the summer of 1927 the collection was transported from Leningrad to Kyiv. The overall weight of the Pototsky’s collections came out to 38 tons with 7 rail cars needed to transport them. The valuable collection was housed in one of the buildings of The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. Pavlo Pototsky began working as a museum staff member and was accommodated with his family in the premises of the Lavra.

However, his arrangements with the Soviet authorities did not prove to be firm. At the beginning of 1934 some of the collection’s pieces were beginning to be expropriated. Pavlo Pototsky began to be subjected to a witch hunt and stigmatization. He was first deprived of an academic allowance, and then his name was excluded from the list of academic researchers. He was facing constant threats of eviction or of his apartment being cut off from electricity and heating. He was subsequently banned from frequenting the museum.

In the summer of 1938 the 81-year-old collector was apprehended on the trumped-up charges of conducting counterrevolutionary activities and preparing terrorist attacks. After a few interrogations and beatings Pavlo Pototsky’s heart collapsed. The official note read, ‘On August 27, 1938 at 13:30 the 81-year-old Pavlo Platonovych Pototsky died of heart failure‘.

At a later point in time, in March 1960, the deputy head of the prosecutor general of the USSR approved the decree according to which, ‘There is no evidence that Pavlo Pototsky put up the struggle against the Soviet authorities’. In September 1960 Pototksy’s good name was rehabilitated. However, it had been consigned to oblivion for a long period of time.

Only beginning from the 1980’s was the issue of charity and philanthropy widely addressed. Ideological bans were finally lifted. Society began to commemorate its renowned philanthropists. Their posterities were offered the opportunity to visit Ukraine. New charitable organizations began to be revived and founded. Meanwhile, country was undergoing an extremely rough transition period and the period of revival of the philanthropic traditions that were in a dire need. However, this is a quite different story.

Sources:

1.Great Soviet Encyclopedia. V.6. 1927 P. 466.Great Soviet Encyclopedia. V. 5. 1950. p. 278

2.A quote from Y. Boiko’s ‘Yehvehn Chykalenko’s work in emigration (1919-1929’) // Ukrainian biographies. 2013 .Issue 10.p. 332

3.Tereshchenko M. The first oligarch: Mykhailo Ivanovych Tereshchenko (1886-1956): An extraordinary life story of my grandfather as it would have been told by my grandmother .Kyiv, 2012. p. 248

4. Quote from T. Miaskova’s ‘Varvara Mykolayivna Khanenko and the fate of her library // Scientific works of the National Library of Ukraine named after V.I. Vernadsky. 2011.Issue. 31.p. 307

5. Bilokin S. The Museum of Ukraine (A collection of P. Pototsky): Research, materials. Kyiv, 2006. p. 57