Even in the context of temporary occupation with enemies lurking everywhere, there is always a place for the good. We have spoken about people, help for others and belief in a swift liberation shared by a woman who is currently residing in Kherson. Here is what she said.

Life before

Originally I am from Kherson. I also lived in Kyiv and Sevastopol, having worked as a photographer. Before that I worked as a manager at a bread baking factory in Crimea. We had no marketing specialist back then and I had to make a new catalog of bread by taking new pictures of it. And that was exactly what I did using a small Olympus camera. I then quit this job and began working as a professional photographer.

I cooperated with Ukrainian designers, participating in different projects. At the beginning of the war I sold my photos in order to help the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Crimea: rejecting Russian citizenship and old friends

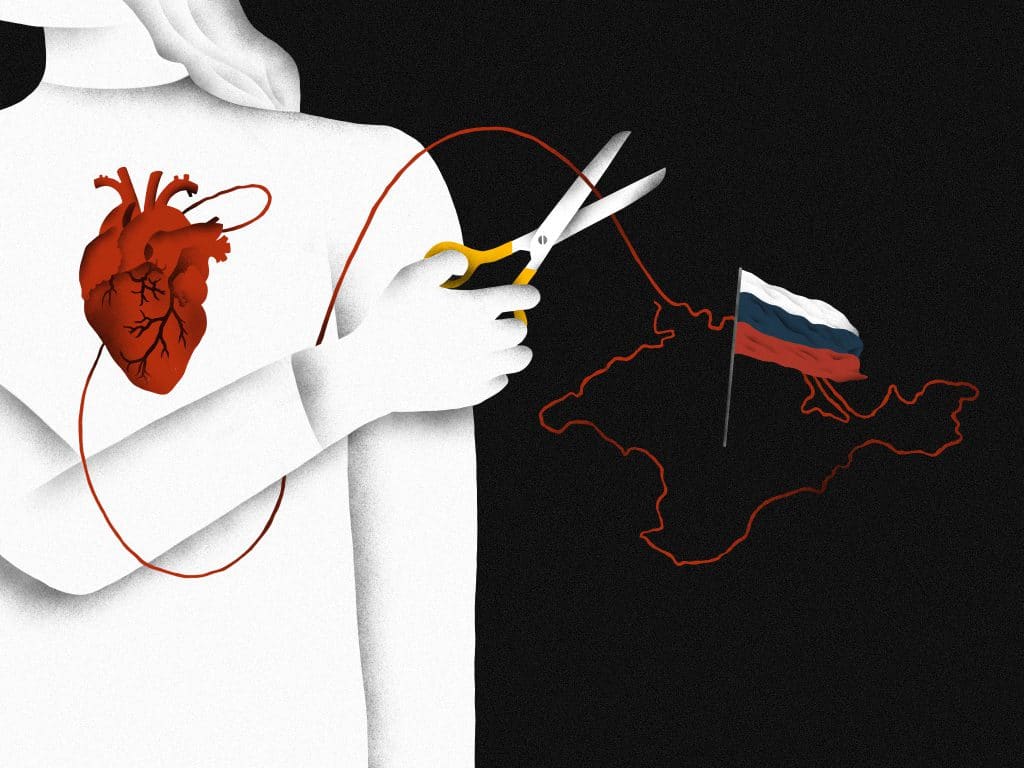

It was the second occupation in my life. Prior to 2014 I had spent 12 years living in Crimea. From the end of February to mid November I lived under Russian occupation. Almost immediately acquaintances and friends of mine, who were pro-Ukrainian, left the peninsula while I stayed.

I remember the demonstration in Simferopol that took place on February 26, 2014 in support of ‚the Russian world‘. My ex-boyfriend took himself there because he was pro-Russian. That led us to break up. A friend of mine (which came as a dreadful shock as at some point in her life she spent 6 months living in my house and receiving help from me) told me she would turn me in to the Russian Federal Security Service should I speak ill of Putin. At some point I realized that in reality I hardly knew these people. We shared absolutely different values.

At that time I was renting a house in the city center. In February some men in uniform began to appear. These were not the infamous ‚little green men‘ (masked soldiers of the Russian Federation in unmarked green army uniforms and carrying modern Russian military weapons and equipment, who appeared during the Russia-Ukraine War in 2014 – translator’s note). Those were men in black looking alike and speaking the same accent. There were many of them. They did nothing special. They were simply watching as if waiting for something. I felt like I was in danger, trying to avoid them. A few weeks later they were gone. I believe they came to Crimea to step in in case developments took a different turn, had more people who shared different views taken to the streets.

After Crimea was occupied, fighting jets began whizzing over my house, preparing for parades. It was really scary. Leaves fell off trees because the jets were flying that low.

In 2014 one would have to sign a special document in order to reject the offer to acquire Russian citizenship. A few days of waiting were required to obtain the document. Russians came up with lots of obstacles – once they said they had run out of paper, on another day they said they had no ink for the printer. After I did get the document and signed it, I published a post on Facebook with a step-by-step guide about how you could turn the citizenship offer down. On that very day over half of my Sevastopol friends unsubscribed from my page.

My political stance was the reason why I was evicted from the house. In the summer of 2014 I became homeless. On a dating site I found a man from Kyiv. He was a movie director, having also participated in the Maidan protests. He just sent me the keys to his summer house in Crimea and I moved in there with my cats. There was often no electricity in the house. Water supply was only available once every ten days. Nonetheless, I learned to chop wood, cooking food on a campfire.

I was intimidated for my pro-Ukrainian position in Crimea. As soon as you published a pro-Ukrainian post on Vkontakte or Facebook, you would be turned in to secret services by your very friends. Secret agents would take people to a forest, dump them on the ground and shoot a few inches away from their heads… It was horrifying. Some of them were subsequently released, and some disappeared for good. But it was not the way things happened in Kherson.

Kherson: things you can never get used to

In November 2014 I relocated to Kherson. I was born in this city. My parents lived there, so I had an apartment to live in. It was here that I experienced my second occupation.

In Kherson more people are disappearing and the situation is worse (than in Crimea – editor’s note). Constant explosions to which you cannot get used. However, we are happy once we learn that our army has hit something. It is petrifying to learn about many searches in people’s houses and flats. People simply disappear. And now, after Bucha and Irpin, Russians do not execute people on the streets. Almost every night there’s hardly any fresh air to breathe because of the stench as if human bodies were being burnt. In the last month the stench has disappeared. It is horrifying to fall asleep at night since there is no knowing whether Russians will come or not.

My mom’s house has been searched a few times. She hid her phone. I am afraid of searches. Russians have already paid a visit to a high-rise building nearby. They searched the house of an acquaintance of mine. They simply came at 3:30 in the morning, climbed over the fence, pointed their guns at my acquaintance’s mother and interrogated her for 4 hours. They dug up the plot of land near the house in search of weapons. Russians climb over fences, come in through windows.

They can also stop you on the street to check your phone. Men are made to undress. I hardly ever take my phone with me outside. We have not had access to mobile connection since May. Someone has bought Russian SIM-cards, whereas I have not. For a few weeks I did not have access to the internet. I do now.

My parents are rather old, my mom is 70 and my father is 75. They live in another district. I can’t leave them. Lots of people have not fled not only because of their parents but also because they do not want to leave their homes to enemies. Russian soldiers occupy them.

At first, buses did not run at all. So I would go to my parents on foot, which took me 3 hours there and back. It was a sketchy undertaking, since I could have come across marauding gangs. At 4 pm the streets were empty.

Also, there was no cash to be had. To withdraw it, one had to go to a shop with wi-fi connection. There was a person that would give you cash (while charging a fee from 7 to 15% of the sum) and you would transfer them money on their card. As for cash, Russian rubles were put into circulation in Crimea in a matter of weeks, while here we still pay for everything with Ukrainian Hryvnia. People do not want to have rubles.

At checkpoints people are often beaten up. Recently a woman driving in a car asked Russians to let her pass quickly. They dragged her husband out of the car and beat him up really badly. They told him to teach his woman to behave as soon as he would come home. They do whatever they want, constantly holding assault rifles in their hands. You get this feeling as if you were raped as soon as they enter a minibus, scrutinizing everyone’s face.

The light of good deeds

When I arrived in Kherson, I only had a handful of friends there. I traveled a lot, so I only would come here to spend winter.

In March we took to the streets to demonstrate, which was a strong emotional experience. There were lots of Russian occupants. All of them were armed. They would form a line and advance on us carrying assault rifles. It was really terrifying. However, people kept standing bravely. I remember us walking to a park so as not to let them shoot a propaganda video. There were snipers everywhere, lying on grass or hiding on rooftops. Everyone was held at gunpoint. Nonetheless, nobody got scared or ran. During the last demonstrations Russians began hurling bombs with tear gas at us. It was impossible to breathe so we had to run.

It turned out that residents of Kherson were kind and compassionate people. Everyone felt empathy and wanted to help with whatever they could.

In their backyard my neighbors feed homeless animals and those abandoned by their owners when fleeing the city. It is now difficult to come by any food products, meat for animals included. However, they manage to find food for them every day, despite the prices having tripled. I give them money as often as I can.

Here we also have lots of older people who have been abandoned.They have problems with hearing and eyesight. Some of them are not even aware of the fact that the war broke out. For example, upon seeing men wearing military uniform, a woman wearing a hearing aid asked me whether some military drills were being held in town. Their neighbors take care of these people. We communicate on Viber. Some of them can bring food, others may call in on the elderly. I know that there are quite a few traitors and separatists, though I have never met them. There are no such people in my circle of friends.

To our backyard people bring mint, grapes, peaches and basil from their plots of land. They support one another with cash. It may seem such a trifle, but it means so much to me.

Those who have access to the internet at home, share their login and password information with neighbors so that they don’t have to make for a shop nearby several times a day and can catch up with news at the entrance to their high-rise building.

People participate in the subbotniks (days of volunteer unpaid work on weekends. This phenomenon was popular in the Soviet Union – translator’s note), cleaning streets and planting flowers. Some bring seedlings or flower bulbs, exchanging and sharing them with each other. My mother also did that. After all the flowers were planted, I noticed that flower beds this year are even more well-kept than the year before.

It’s much easier when you live ‚here and now’, concentrating on the future while keeping yourself busy.

Switching to Ukrainian

I had a complex before (before 2014 – editor’s note). I thought that when I read aloud in Ukrainian everyone wanted me to shut up as my pronunciation was not the best. I think it looked like someone singing out of tune.

I always liked Ukrainian. I wanted to admire it and let it mesmerize me. However, I never tried to speak it because I felt embarrassed about my pronunciation which was far from perfect.

After Crimea was annexed in 2014, I began to reject all things Russian. I almost stopped watching films dubbed in Russian, switching to English or Ukrainian. I also did away with Russian music which made me sick. At the same time I switched the language on my devices to Ukrainian or English. However, I still felt comfortable conversing in Russian. I switched to either Ukrainian or English only when going abroad. Coming across Russians abroad, I did not want them to think I was one of their folk.

A few weeks after February 24 I came to understand that I did not want to speak Russian any longer. This was my inner feeling. I felt aversion to speaking the language of our enemies, especially after the massacres in Bucha, Irpin and Mariupol. I felt that I did not care just how imperfect my Ukrainian was.

At first I began using Ukrainian while texting. I asked everyone whom I texted to correct mistakes should they spot one. In the beginning I had this feeling that I was lacking words. However, I look up words in the dictionary of synonyms, which is helpful. I then started speaking Ukrainian in shops to shop assistants whom I did not know.

In Kherson almost everyone responds to you in Ukrainians if they are addressed in this language. This helped me overcome the language barrier. Then I began talking to two Ukrainian-speaking friends of mine who supported me in this endeavor. At first it was difficult, but it is a matter of habit, after all. They did not laugh at me. They corrected my mistakes. I still speak Russian with my relatives, although I text them in Ukrainian. For me this is perhaps the hardest step I have taken.

In general, while gradually switching to Ukrainian, I feel some change inside as though I were becoming a softer, more polite and sensitive person. I don’t simply describe events, I fill them with emotions.

Hoping for liberation

On some days you get this feeling that nobody will ever liberate us, that Kherson will be destroyed by bombs just like Mariupol, that there is no place to run to and you are trapped facing the enemy all by yourself. At times I lose all hope and there is nothing I could hold on to. All my hopes seem ephemeral.

After Olenivka (a tragedy that occurred on 29 July 2022, when a building housing Ukrainian prisoners of war in a Russian-operated prison near Olenivka, Donetsk province, was destroyed, killing 53 Ukrainian prisoners of war and leaving 75 wounded – translator’s note) and Mariupol, after we learned about what happened to our prisoners of war, people stopped leaving their homes. After this news I fell into despair, being left in the dark. It is hard to get yourself out of this predicament. However, something had to be done about it. I needed to carry on doing what I had been doing before. Once your spirits get low, you are doomed.

Yoga is enormously helpful when it comes to keeping afloat, as well as mediation and physical exercise. I do as many push-ups as I can until I don’t have any strength left to feel any emotions. I just want to lie down and never have to get up, but this will be a fatal mistake. I will never extricate myself from it.

My 70-year-old mother does yoga with me. She gets tired of it but her mood is stable.

Every day I get messages from friends and relatives residing in the Ukrainian government-controlled territories asking me how I am doing. They offer me strong support. Without them things would be really tough. We had a feeling that we did not exist. Every day I count things which I am grateful for: the fact that I am still alive, that my parents are alive and not sick, that I have a place to live at and food, that I have wonderful friends who work and donate for unmanned aerial vehicles to be purchased. I am happy when the Ukrainian Armed Forces receive high-quality weapons, making advances towards Kherson. I am happy when our enemy is sustaining heavy losses.