What did students of the previous century call ‘a happy and a free ticket to life’, what kind of work did they look for and with the help of what philanthropists did they receive education?

Nearly 150 years ago the rector of the Kyiv University Mykola Bunge pointed out that more and more students applied to the university’s management for financial assistance. In 1872 he decided to do research on students’ everyday life by conducting a survey. Even the rector himself was taken aback by its results.

It transpired that over 60% considered themselves as poor, indicating that they were short of money to afford even bare necessities.

Near the end of the 19th century the situation deteriorated. More and more youths from non-affluent families were enrolling at universities in the hope that higher education would play the role of a ‘social elevator’ that would free them from penury. More often than not these hopes were never fulfilled. At the beginning of the 20th century, about 70-80% of students in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa regarded themselves as poor and unprovided for.

The assistance from the state could barely cover the needs of the students: state scholarship allowance was indeed granted, however, to the very few. On top of that, the students had to work their allowance off after graduating from university. The regular 4-year course of study would mean that the student had to spend 6 years working the scholarship allowance off, in which case their place of employment was selected by the officials from the Ministry of Education.

It was a tall order to make one’s living while studying at the university. The main work that students could do was private tutoring, which was a low-paid activity. An increasing number of students meant smaller fees and fiercer competition. It is not for no reason that one could frequently come across an ad in the classifieds of the newspaper published in one of the university cities that read, ‘Looking for a job of a tutor. Any conditions will do’.1 Charitable assistance was virtually the only way for hundreds of students to receive education.

Private scholarships

One of the common ways to help students was to grant them private (often named after its donor) scholarships. The mechanism was quite simple – a benefactor or a group of initiators or a certain organization would send a request to an education institution offering to launch a scholarship. To this end, a deposit would be put down in a bank (usually such a deposit amounted to several thousand rubles). This sum remained untouched with the annual interest rate used for funding one or several scholarships granted to selected students. Normally, private scholarships imposed no onus on students. For them they were ‘a happy free ticket’ to life.

Each of the private scholarships would be approved by the minister of education and they were granted by the administration of an education institution to those whom it may have concerned. Those students who wanted to get such a scholarship had to submit a request to their dean, who would then select the most relevant requests and forward them for consideration of the council of a respective institution. In addition, the dean attached background information on students’ performance and a certificate of their exemplary behavior. The council would then decide to whom the scholarship was to be granted. The scholarship was awarded for a period of one year and the procedure had to be repeated on an annual basis. In case a student flouted the rules or failed interim exams, the scholarship was canceled.

From professors with love

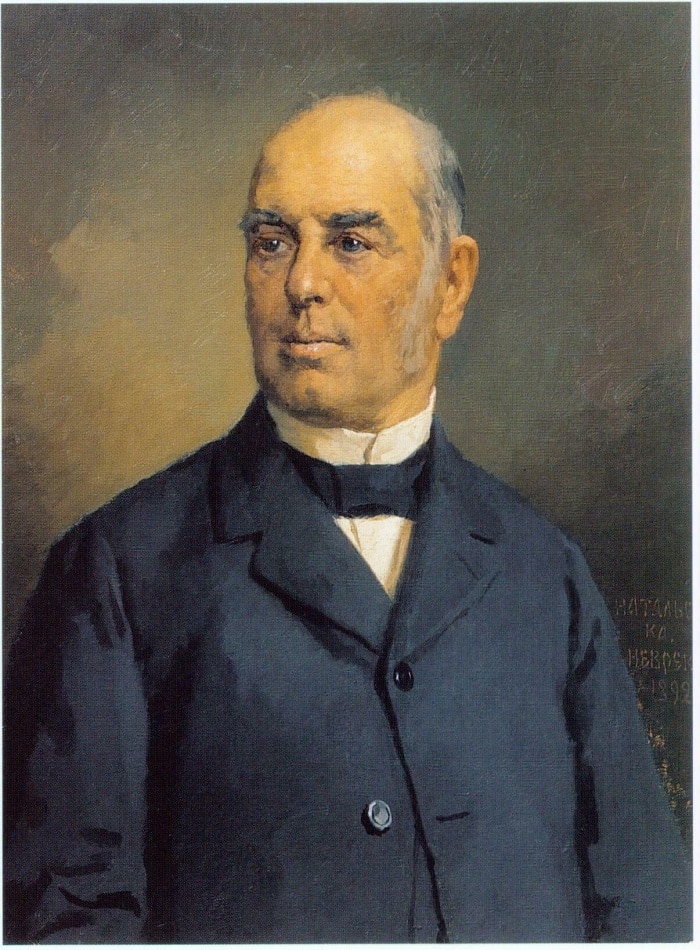

Usually professors at universities were the first to take notice of the students’ financial predicament. For their part, they tried to help them. It is for this reason that the first private scholarships were awarded by professors. On a related note, this scholarship was awarded to the student of the Kyiv University, Yevhen Tarle, the future renowned historian of the history of France during Napoleon’s reign.

Other benefactors pursued different motives regarding the establishment of such scholarships. A case in point was the famous Ukrainian entrepreneur and philanthropist Ivan Kharytonenko who regarded it as his personal duty to foster the development of education. In 1885 he donated 50 thousand rubles to the Kharkiv University. The interest rate obtained from this sum sufficed to launch 20 scholarships of 300 rubles each. On the other hand, an alumnus of the Kyiv University, who did not wish to be named, donated 950 rubles to the establishment of a modest scholarship of 50 rubles for the most indigent student of the university. Apparently, this benefactor had to endure a difficult life of a student himself, which is why he decided to provide help at least for one of the students in Kyiv.

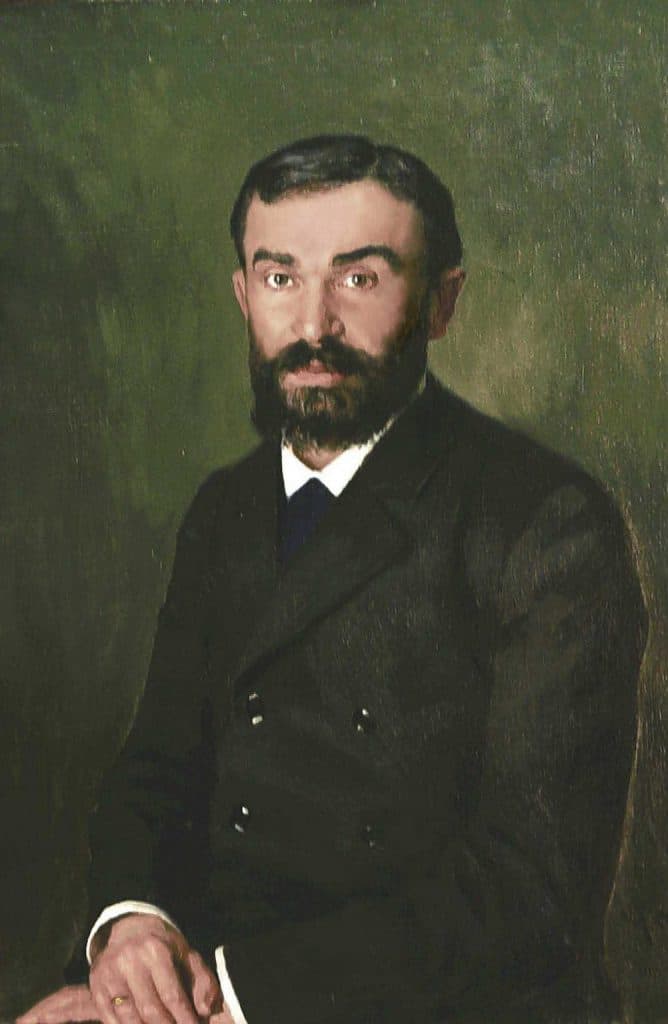

Oftentimes scholarships were financed from the capital bequeathed according to someone’s will. For example, a high-ranking official Hryhoriy Bykovskiy stated in his will that he desired to bequeath all his fortune to the students of the Kharkiv University. It was a handsome sum of 100 thousand rubles. As a result, 16 students would be awarded the annual Hryhoriy Bykovskiy scholarship. Another case in point was Ivan Yahnytskiy, a retired military man, a successful entrepreneur and a partner of the firm ‘Yakhnenko and Symyrenko brothers’. In his will Yahnytskiy donated 20 thousand rubles to the Odesa University, thanks to which four students of the university would be given an opportunity to have their education costs covered.

Education ‘in memoriam’

It also so happened that family members would launch a new scholarship in memory of their late relative. This was the case with the Tereshchenko family.

After Ivan Tereshchenko’s death following tuberculosis complications his widow, Yelyzaveta, made a donation of 30 thousand rubles to the Kyiv University. The money was used for the launch of three scholarships named after Ivan Tereshchenko. In order to let you realize just how big the sum was, keep in mind that a dairy cow cost 40 rubles at that time, with 35 pounds of sugar going for 5 rubles. In other words, for this money one could have bought 750 cows or 96 tons of sugar.

There were also more pragmatic reasons for founding a scholarship. For instance, after the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute (KPI) was founded, it was said in reports that ‘the material security of students is quite meager, just as it was last year. While working from early in the morning till late at night on practical tasks at the Institute, they don’t have spare time to make money as tutors’.2

The entrepreneurs who were involved in the establishment of the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute and who were in need of staff for their plants, had to also support the unprovided for. It was a sort of investment into youths that had to be paid off quite soon. For example, the famous entrepreneurs Lazar and Lev Brodskiy donated 18 thousand rubles in the form of scholarships to the students of the Institute. Another businessman, Mykhailo Dehtiarov, made a donation of 15 thousand rubles for the underprivileged students of the KPI.

Private scholarships were an effective way to tackle students’ poverty. However, their number could not turn things around for the better. Thus, there were over 90 scholarships available in the beginning of the 20th century at the Kharkiv University that covered the needs of more than 150 students who made up a mere 3-4% of the total number of the students.

Public charity

Not only did professors at universities found private scholarships for talented youths, they would also set up the initiative for launching various fellowships, committees or funds that would provide aid to students. The idea of such organizations was quite simple – its founders would invest a seed capital and try to attract as many participants as possible who would then donate more money.

By means of these funds such fellowships attempted to solve students’ main everyday problems. First of all, these organizations were helping to cover education costs as well as providing financial aid. For instance, students in need were offered regular or one-off loans, a sort of mini credits. These loans were to be paid off after the completion of study, as soon as the graduate found work and had access to stable income.

Originally such a system was working fine. However, it failed as time passed. Students were eager to take loans out, but their repayments turned out to be few and far between. Therefore, effectively all charitable unions were facing a huge budget shortfall. For example, between 1881 and 1905 there were 1253 debtors at the Fellowship of Aid for the students of the Kyiv University alone, whose debt amounted to 75 thousand rubles. It was then that these organizations began to resort to drastic measures of launching debt committees whose task was to find the indebted alumni and to collect their debt in court. Such practice did bear fruit. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the 20th century the vast majority of public organizations, which were providing aid to students, had run a deficit of dozens of thousands rubles.

Things looked better in terms of providing material help. First of all, the most indigent students were provided with food. For instance, one organization set out a goal of ‘mitigating penury, depriving students of the most terrible consequences of poverty, of the nightmares of degeneration caused by famine, preventing students from starving to death’.3 For this purpose, students were offered free lunches and discounts at refectories.

Another way of helping poor youths was distribution of clothing and footwear. Charitable organizations also helped students with educational materials and medicines. The start of the 20th century saw the advent of labor and housing offices for students. Such organizations were also searching for different side job options for youths or cheap apartments for the most destitute.

Aside from various donations and member fees, students and the public also engaged artists in helping the former. Dozens of charity concerts, theater performances and dancing events were held for the benefit of the unprovided for students.

One of such charity evenings featuring a concert and a ball was described in her memoirs by the writer Zinaida Tulub, ‘The concert was divided into two parts. It began at 8 pm or thereabouts… After the concert at around 11 pm the dancing part commenced accompanied by two orchestras. The club was packed out by professors and their wives, students, state officials, military people, even generals, lawyers, doctors and engineers. It was so much fun there… The ball would end in the small hours of the next day. Our net profit would come out to 1,5-2 thousand rubles’.4

Self-help by students

There were a great many charitable initiatives for the benefit of the community of students. However, the rule of thumb for most of them could be described with the help of the saying ‘if you need a helping hand, you will find one at the end of your arm’. Therefore, students would establish students’ organizations.

First of all, these were different associations of fellow-countrymen whose task was to provide aid to their members. Their charters often stated that these associations were founded with a view to ‘meeting the material and cultural needs of students’.

Alongside these associations, the student cooperatives were beginning to appear, which were opening their ‘social shops’ up where students could buy bare necessities at a reduced price.

For instance, students from Poland launched a fund at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute which they symbolically named ‘Fraternal assistance’.

The participants of the organization helped one another financially, looked for tutor jobs together and shared books and course books with one another. Students had understood it from time immemorial that it was much easier to overcome hardships in cooperation with friends.

The modern life of students has become much more comfortable and easier in many respects. They are now faced with challenges of a totally different order. However, this is not to say that students are not to be supported or encouraged. In my view, the foundations of private scholarships or various fellowships for the benefit of students has not lost its relevance, since to help them means investing in the future.

Sources and literature:

- Кryvonosov T. Helping youths: a collection of articles, letters and notes on students’ needs and suicides among them. Kyiv, 1910. P. 236).

- The 1904 report of the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute named after Alexander ІІ. К., 1906. p. 67).

- Kryvonosov T. Helping youths: a collection of articles, letters and notes on students’ needs and suicides among them. Kyiv, 1910. p. 239).

- Tulub Z. My life. Kyiv, 2012. P. 276-277

- Kruhliak M. Everyday life of students of the Russian-governed part of Ukraine in the second half of the 19th, the beginning of the 20th century. Zhytomyr, 2015. 464 p.

- Hrebtsova I. The Novorossiya University in the development of charity in Odesa (the second half of the 19th – the beginning of the 20th century). Odesa, 2009. 504 p.

- Stupak F. Charitable fellowships in Kyiv (second half of the 19th – the beginning of the 20th century). Kyiv, 1998. 220 p.

- The rules for scholarships, allowances, prizes and other awards at the Imperial Kharkiv University. Kharkiv, 1913. 136 p.